The (Not-So-Secret) War on Moms : How the Supreme Court Took Protections Away from Pregnant Workers

This week, the Supreme Court ruled, by the all-too-familiar 5-4 margin, that a provision of the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) giving workers time off to care for their own serious health conditions — including pregnancy and childbirth — can’t be enforced by state employees in damages lawsuits against their public employers. The decision in Coleman v. Court of Appeals of Maryland effectively stripped many public employees — the majority of whom are women — of the right to job protection when they need to take time off while pregnant. The ACLU had joined an amicus brief arguing that the law was written in a gender-neutral way to provide women workers with the time they needed to go through childbirth and pregnancy-related complications, while ensuring that employers wouldn’t discriminate based on the assumption that only women will need to take health-related leave from their jobs. While no opinion garnered five votes, a majority of the Court agreed that the law was not justified as a remedy for a pattern of unconstitutional discrimination against women or pregnant workers.

What’s noteworthy about the decision is Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s dissent, which she summarized aloud from the bench — an indication that she felt strongly that the majority had royally missed the point. In an opinion nearly twice as long as the plurality’s, Ginsburg placed the FMLA in the context of a decades-long struggle for women’s equality in the workplace. The FMLA — including the self-care provision — was drafted as a gender-neutral response to the fact that previous legislative victories, including the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, which amended the civil rights laws to forbid job discrimination on the basis of pregnancy, had not succeeded in preventing discrimination against pregnant workers. Then, as now, pregnant workers were being pushed out of the workplace. Then, as now, women were told they should stay home after having children. And then, as now, women who took maternity leave paid a heavy price for doing so.

But did all of this discrimination against pregnant workers amount to unconstitutional sex discrimination? Five justices seem to think not — the plurality in Coleman denied that the self-care provision of the FMLA had anything to do with sex discrimination, even while admitting that the provision benefits pregnant workers.

In dissent, Justice Ginsburg attacked this view, arguing that it is based on a much-criticized Supreme Court case from 1974 holding that governmental pregnancy discrimination is not unconstitutional sex discrimination. The case is Geduldig v. Aiello, and it held that, even though only women can become pregnant, a disability insurance program that excluded pregnancy was lawful, because it discriminated between “pregnant women and nonpregnant persons,” including both men and nonpregnant women. Ginsburg called upon the Court to “revisit” that dubious conclusion, and bring its rulings into accord with the common-sense understanding that pregnancy discrimination is a form — if not the quintessential form — of sex discrimination.

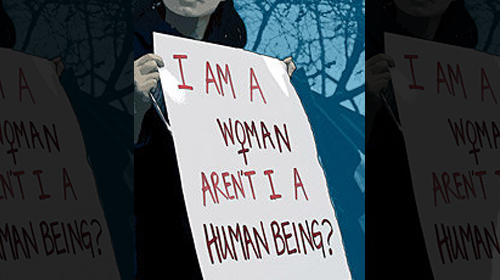

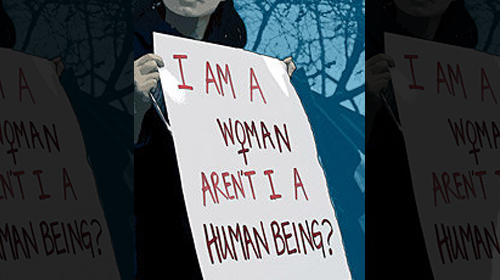

As Justice Ginsburg pointed out, pregnancy and the capacity to become pregnant have always provided the “central justification for the historic discrimination against women,” not only in the workplace, but in other spheres, and not only by private employers, but by the government through laws that curtailed women’s opportunities and civic life. Mothers, pregnant women, and any woman whom an employer suspects might become pregnant have always been on the front lines of the war on women — and they still are. New mothers are vulnerable not only to being fired, but to being kicked out of school, humiliated, and even, when they breastfeed, banished from the public sphere. Stripping job protections from pregnant workers invites discrimination against women — a reality that was clearly understood by the three women justices who dissented.

Learn more about women’s equality in the workplace: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.